Bathhouses

The Japanese have always been noted for their neatness, meticulously cleaning their homes and maintaining strict personal hygiene habits. In the 17th century, communal baths gained widespread popularity in Edo. Houses were very cramped, their residents had to save on everything, and the urban supply of fresh domestic water took some time to be established.

As in other cultures, bathhouses performed not only the role of communal washrooms, but also of clubs of sorts. These were public sitting pools with very hot water, by European standards. The design of the bathhouse buildings ensured that lighting was dim. As well as this, men did not take off their waist-cloth while in the water, and women kept their undershirts on. In any case, the dense vapour filling the washrooms obscured the gender of one’s fellow bather, as well as the cleanliness, or otherwise, of the water.

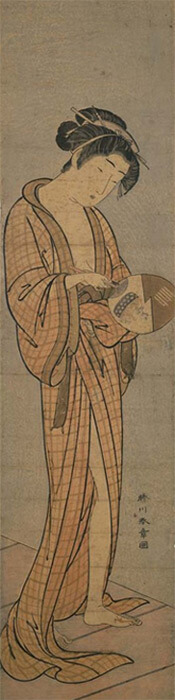

Katsukawa Shunshō

Woman with Fan after Bath